What is required for long-term change? Our Safe Routes to Parks Activating Communities program is all about making changes, big and small, to make park access safe, convenient, and equitable for people walking and biking. However, we know that making changes to a sidewalk or holding one community engagement meeting isn’t going to have as long-term of an effect if we don’t zoom out to see the whole system that created unsafe routes or inequities in the first place. This can be complicated, but a good tool that we have been using to think about this is a “systems change” model adopted from FSG.

FSG is a consulting firm based in Seattle, Washington that created a systems change framework focusing on identifying the conditions that hold a problem in place and how to meaningfully shift them in pursuit of a more equitable future. 1 They liken these conditions to the water in this story:

“A fish is swimming along one day when another fish comes up and says “Hey, how’s the water?” The first fish stared back blankly at the second fish and says “What’s water?”

Conditions can be invisible to people experiencing them every day. Whether or not they are noticed, these conditions can hold significant problems in place. Without addressing them, we can’t change the system and the outcomes it produces. It is important to note that these conditions are not independent of one another. They can reinforce one another (a decision maker’s shift in mental models could lead to different resource flows) and even counteract each other (a new practice could be ineffective if you are missing strong enough relationships to implement it). 2

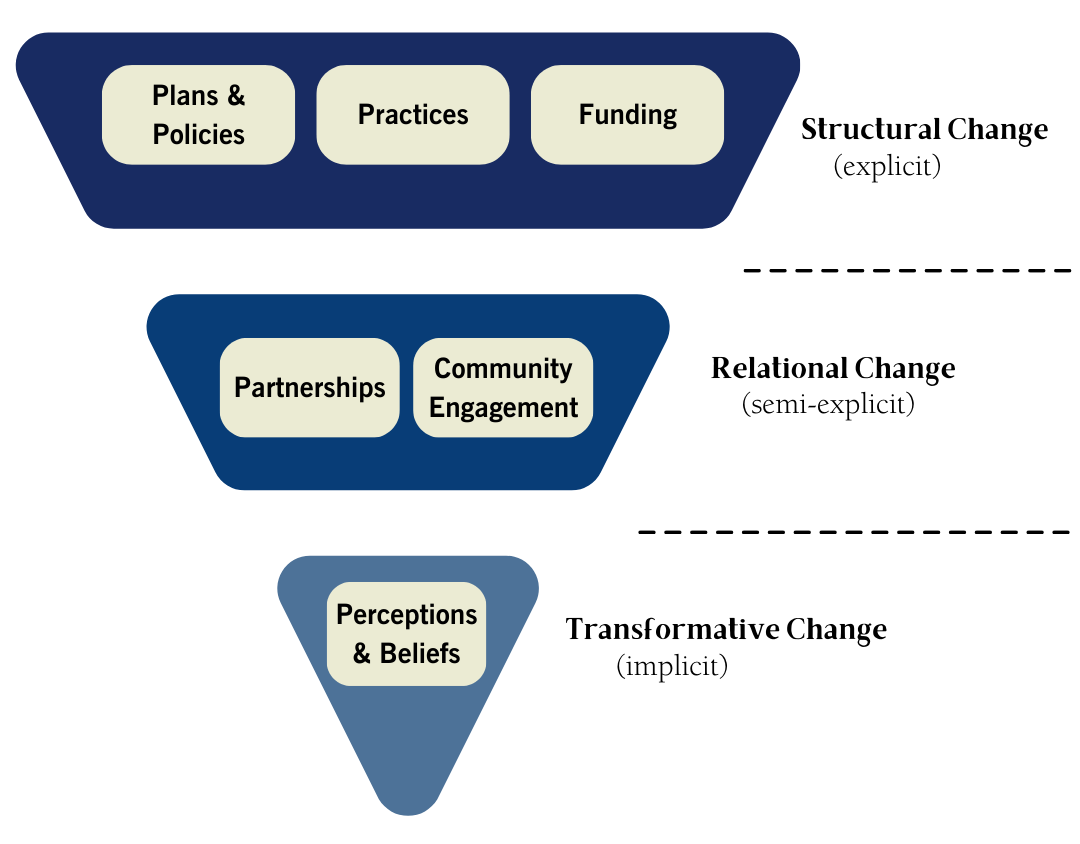

Our program’s goal is to increase equitable park access by dismantling systems of inequity through systems change so here is how we have defined the different elements in FSG’s model.

- Plans & Policies: Update the rules, guidelines, and lists of projects that guide both government agencies and community organizations so that they include safe and equitable access to parks.

- Practices: Expand programs and standard operations to include activities that support equity and Safe Routes to Parks. Examples could be new data collection strategies, using data to inform where route improvements connect to parks, or scheduling events in park spaces that are accessible by biking, walking, and/or transit.

- Funding: Allocate funding as well as staff and volunteer time to make parks safer and easier to access via walking and biking. Prioritize that funding based on equity.

- Partnerships: Work with a variety of partners that represent different parts of the community to advance park access like public health, transportation, parks and recreation, schools, faith communities, and volunteer groups.

- Community Engagement: People are experts on the places they live, so make sure they are influencing decisions to address park access needs.

- Shifting Perceptions and Beliefs: Expand commitments to safe, convenient, and equitable park access. Change preconceived notions and in-grained ways of thinking.

To help ground all of this in tangible projects, we have included videos from past Safe Routes to Parks grantees with notes about some of the areas of systems change that they addressed as part of their projects (whether they were thinking about it that way or not).

Safe Routes to Cully Park in Portland, Oregon (video)

This video features community members in the Cully Neighborhood of Portland, Oregon installing a wayfinding system to incorporate maps, signs, and community art that resonates with and is designed by the people of color and low-income communities within the neighborhood.

What can we learn from this project?

- Community engagement: Living Cully, the lead organization, hosted a workshop on wayfinding and community members worked with bilingual artists to identify symbols that could represent each park. They engaged youth and family members to get broad input on routes to and from Cully Park.

- Shifting Perceptions and Beliefs: Living Cully hosted a total of 21 events to engage community members on routes and wayfinding to Cully Park, inviting people to be part of this co-creative process helped build community ownership and stewardship.

Safe Routes to Parks Tactical Urbanism in Birmingham, Alabama (video)

This video highlights a pop-up bike lane demonstration project in the historic neighborhoods of Titusville & Smithfield of Birmingham, Alabama to show how bike lanes could be utilized to connect to local parks and green spaces.

What can we learn from this project?

- Partnerships: Community residents, leaders, bike share operators, and the City of Birmingham came together to plan and implement this demonstration project.

- Community Engagement and Practices: Survey results from the demonstration project showed interest and demand to make a bike lane permanent on Center Street. This made the case to the Department of Transportation who restriped the street to make this a permanent bike lane.

- Shifting Perceptions and Beliefs: Some community members who used the pop-up bike lane had not ridden a bike since they were a kid! By trying out this safer, more comfortable route, they could envision biking as a way to get to their local parks.

Hyati Heritage Center Safe Routes to Parks in Durham, North Carolina (video)

The Hayti neighborhood in Durham, North Carolina was once a prosperous black neighborhood, but was bisected by a freeway in the 1960s. This video shows how residents are creating safer walking connections in their community, starting with a colorful, culturally significant artistic crosswalk.

What can we learn from this project?

- Practices: The organizers do a walk audit to understand what residents want and need for safer walking conditions. This is a useful practice for centering community members’ priorities.

- Community Engagement and Shifting Perceptions and Beliefs: In the video, one of the project participants shares they hope people feel a great deal of pride when they pass the colorful crosswalk because of how they have contributed to their community. Engaging with community members from the beginning of a project increases their sense of ownership over the final product. This process of engagement and follow-through also helped underscore the belief the community members should be the ones who decide how they are able to move through their neighborhood.

Creating Safe Routes to Parks in Greenfield, California (video)

This video highlights an event that drew attention to physical access to the park with a temporary crosswalk and biking lane while also activating the space with activities like Zumba, a color run, and a pop-up bike course.

What can we learn from this project?

- Practices: Activating park space can help draw attention to access issues and get more people invested to support improvements.

- Community Engagement: This project was particularly successful at showing that residents can have an influence and contribute to work in their neighborhood, especially young people.

Friends of McAllister Park Routes to Equity in Lebanon, Illinois (video)

The video outlines the activities that Friends of McCallister Park did to build energy and excitement for creating safer routes to their park, building a trail, creating the Routes to Equity plan, and increasing momentum for a larger neighborhood plan.

- Plans and Policies: They are showing how you get buy-in and do engagement over time to create plans that are well-grounded in what the community wants.

- Practice: The video shows many different engagement events and opportunities for data collection. This shows how much fun it is to move past traditional town hall meetings!

- Community engagement: Friends of McAllister Park