The July 4th weekend brought all of the flare and celebration that we expect every year; celebrations of freedom and opportunity that ideally we all should have and enjoy. Unfortunately, while many Americans around the country gathered to eat barbeque and watch the fireworks, families and friends in Chicago ran and cried as pops and flashes riddled the city. A total of 82 people were shot over the July 4th weekend.

The July 4th weekend brought all of the flare and celebration that we expect every year; celebrations of freedom and opportunity that ideally we all should have and enjoy. Unfortunately, while many Americans around the country gathered to eat barbeque and watch the fireworks, families and friends in Chicago ran and cried as pops and flashes riddled the city. A total of 82 people were shot over the July 4th weekend.

Many stories have surfaced in the past weeks, but I wish to highlight one – that of 17-year-old Marcel Pearson, whose story was noted in the Chicago Tribune. In just two days, his mentor was supposed to be driving him four hours to his freshman orientation at Western Illinois University. On July 4, he was walking with friends in Robichaux Park in the Brainerd neighborhood when a white van pulled up and started shooting. Pearson never made it to orientation. Instead, his family gathered as he lay covered in a white sheet, only blocks from his home, dead, with wounds to the chest and back.

Protecting our youth is an issue that cannot be ignored. If we believe that every child should be able to freely live, walk, work and play in their neighborhood, then community safety advocates must become fluent in the language of healthy community design, and built environment advocates can no longer be afraid to hold hands with community safety advocates.

Discussions around the country of effective strategies and innovative partnerships have become more consistent, but we can do more; we need to do more for kids like Marcel.

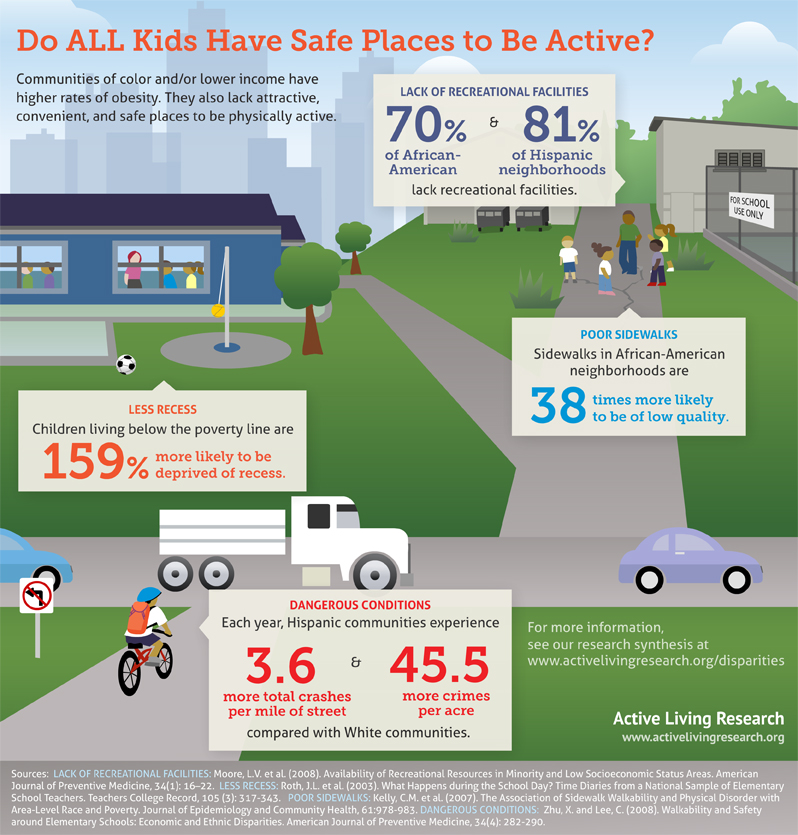

Studies show that “lower-income and racial and ethnic minority people tend to live in neighborhoods with fewer and poorer quality sidewalks, fewer parks and open spaces, and more crime, social disorder and traffic.” Each year, Latino communities experience 45.5 more crimes per acre compared with White communities and parents report violence and crime as one of the five primary factors affecting children's walking or biking. With pedestrian injury being the leading cause of unintentional, injury-related death among children age 5 to 14, it’s not surprising that Latino and African American children are 40 percent and 50 percent more likely than their white peers to be killed while walking.

Studies show that “lower-income and racial and ethnic minority people tend to live in neighborhoods with fewer and poorer quality sidewalks, fewer parks and open spaces, and more crime, social disorder and traffic.” Each year, Latino communities experience 45.5 more crimes per acre compared with White communities and parents report violence and crime as one of the five primary factors affecting children's walking or biking. With pedestrian injury being the leading cause of unintentional, injury-related death among children age 5 to 14, it’s not surprising that Latino and African American children are 40 percent and 50 percent more likely than their white peers to be killed while walking.

The lack of safe space to walk, bicycle, or be outside in a community has a direct impact on physical activity levels, job access, education options and housing quality. Advocates for physical activity and healthy community design realize that focusing on eradicating violence and crime in underserved neighborhoods is a necessary precursor to improving access to physical activity and improving the quality of life.

Over the last year, the Safe Routes Partnership has stepped out to make the improvement of underserved communities a key priority. We are determined to break the barrier between community safety and built environment advocacy, with action steps such as establishing two diverse national task forces, partnering with the NAACP to create an equity asset map of resources/funding/capacity throughout the country, developing policy, coalitions and funding capacity in states and local communities, and partnering with organizations like NOBEL-Women (an association of black women elected officials) to pass policy resolutions on health equity and safety.

These issues are a matter of social justice and are interdependent if a healthy, accessible, and affordable place to live is something every American should be able to obtain. In the words of my favorite writer James Baldwin, “too many young people are growing into stunted maturity, trying desperately to find a place to stand; and the wonder is not that so many are ruined but that so many survive.” We need to create new partnerships to ensure survival for young people like Marcel Pearson, but also to go beyond mere survival. By working together, we can create safe places that let young people, and all of us, thrive.