This blog post was authored by research advisor Tiffany Lam.

Collectively, there is an attitude that traffic crashes “just happen” and are inevitable, as unfortunate as that may be. Vision Zero turns that idea on its head by arguing that no one should be injured or killed while moving around their community regardless of their mode of travel. The chief tenet of Vision Zero is that we cannot accept traffic deaths and injuries as a fair exchange for personal mobility, and that we, as a society, have an ethical obligation to keep people safe from road traffic danger. Vision Zero has been gaining traction in US cities over the past four years and is a growing global movement that was first enshrined in policy in Sweden in 1997.[1] Like Safe Routes to School, Vision Zero is a comprehensive campaign that aspires to improve safety and mobility, and cities across the United States are embracing it.

Given that communities of color and communities with lower-incomes are disparately impacted by traffic-related injuries and fatalities, cities working toward Vision Zero have the potential to rectify active transportation inequities. However, some cities are over-relying on police enforcement to achieve their Vision Zero goals, which disproportionately disadvantages low-income communities of color, has raised serious equity concerns. To fulfil its potential to ensure safe, healthy, sustainable, and equitable mobility for all, cities working to implement Vision Zero must understand and address these concerns and employ the comprehensive set of strategies promoted by the Vision Zero movement.

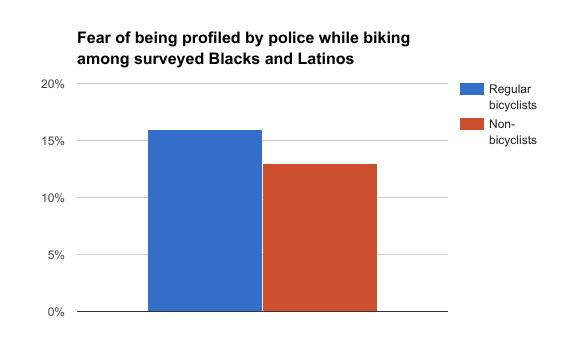

Police-officer-initiated traffic enforcement is a longstanding tool to improve traffic safety. Compared to changes in street design and engineering, it’s easier, less expensive and time-consuming, and it requires less political will to implement. A recent Rutgers University study reveals the unintended consequences of relying heavily on enforcement by showing that racial profiling and police harassment are barriers to bicycling for Black and Latino men. As the graph below illustrates, these fears are heightened among Black and Latino men who bike.[2]

This suggests that increased police enforcement may aggravate existing fears of racial profiling and police harassment among Black and Latino men. It is unknown whether this will make Black and Latino men who already bike stop bicycling, though it will certainly create a more hostile environment. It may also make Black and Latino men who don’t already bike less inclined to start bicycling.

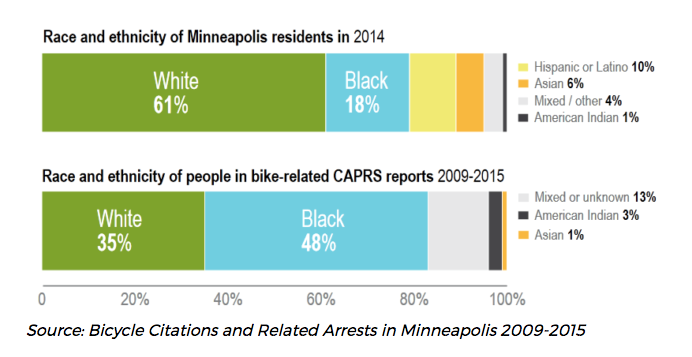

Research from Minneapolis, Tampa, and New York has evidenced racial disparities in bicycling citations, whereby Black cyclists receive higher rates of official incident reports and citations compared to white cyclists. As shown below, despite comprising just 18 percent of the total population in Minneapolis, nearly half of those who had an incident or arrest report after being stopped for a bicycling citation were Black.[3] Increased enforcement may increase racial profiling and exacerbate tensions between police and communities of color, providing another reason to be wary of relying on this tool.

If cities lack the political will to make necessary changes in street and road design and speed management that are the most effective way to implement Vision Zero, they may rely too heavily on enforcement as the primary mechanism for achieving its goals. This problematizes the sanctuary city status of self-identified cities, like San Francisco and New York. In February, the Department of Homeland Security expanded rules targeting immigrants for deportation to include traffic violations. The San Francisco Vision Zero Coalition issued a statement in February denouncing these new rules, stating that just as Vision Zero cannot be misused to justify racial profiling, it cannot be perverted into an excuse to deport undocumented immigrants.

Similarly, the Biking Public Project in New York has decried the over-policing of delivery cyclists, who are mostly people of color and immigrants with potentially precarious immigration status. Delivery cyclists work physically demanding, low-wage jobs that require them to be out and about on unsafe streets. Enforcement in the name of Vision Zero cannot be an excuse to penalize and further marginalize vulnerable New Yorkers who are simply trying to do their jobs.

While better engineering will ideally diminish the necessity of enforcement, advocates must also consider how engineering standards of road traffic safety intersect with broader notions of safety (i.e., safety from racial profiling and police harassment, safety from sexual harassment, etc.). For instance, streets with wide sidewalks, safe intersections, and traffic lights that provide ample time for people to cross the street will likely offer adequate protection from road traffic danger, but insufficient street lighting could make it feel unsafe for women, especially at night. Similarly, engineering improvements can make streets safer from road traffic, but if there is frequent police presence, this may make people of color feel the need to take an alternative route to avoid potential police interaction.

This is all to say that while road traffic safety may be more easily objectively measured (i.e., traffic crashes, injuries, and fatalities), people’s perceptions of safety are subjective, qualitative experiences that don’t enter into engineering discourse and practice. The risk, then, is that road safety gets reduced to a technical engineering problem while omitting other important aspects of personal safety (i.e., safety from crime, safety from harassment and violence, etc.) that impact people’s daily mobility.

Structural inequities in society at large get reproduced in transportation. At the May 2017 Vision Zero Cities Conference in New York, Tamika Butler, former Executive Director of the Los Angeles County Bicycling Coalition, gave a passionate speech about whether Vision Zero can work in a racist society. Without an explicit confrontation of racism in transportation/urban planning and policy, cities working to implement Vision Zero will not succeed in achieveing the goal of zero traffic deaths. As advocates of safe, sustainable, healthy transportation, we have a role to play and a responsibility to ensure that our work challenges and dismantles structural inequities rather than reproducing and reinforcing them.

[1] Elvebank, Beate. “Vision Zero: Remaking Road Safety.” Mobilities 2, no. 3 (November 2007): 425 – 441. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17450100701597426.

[2] Cox, Stefani and Charles Brown. “Silent Barriers to Bicycling, Part III: Racial Profiling of the Black and Latino Community.” Better Bike Share Partnership. March 3, 2017. Accessed August 13. 2017. http://betterbikeshare.org/2017/03/03/silent-barriers-bicycling-part-ii….

[3] Cox, Stefani. “Could the Challenges of ‘Biking While Black’ Be Compromising Bike Share Outreach Efforts?” Better Bike Share Partnership. November 8, 2016. Accessed August 13, 2017. http://betterbikeshare.org/2016/11/08/difficulties-biking-black-comprom….